The new year was supposed to be a celebratory moment for the U.K. After growing 2.9 percent in 2014, the fastest pace among G7 economies, and 2.2 percent last year, 2016 was to see that recovery become established, particularly for workers.

Instead, the consumer engine that's powering the economy is running on the fumes of low oil prices.

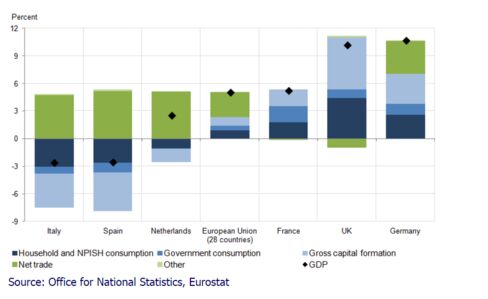

Following the Great Recession, the U.K. consumer has helped pull the country from its slump. Between 2009 and 2014 household consumption contributed 4.3 percentage points to GDP growth, far more than consumers in countries such as Germany, where growth was balanced between trade, investment and household spending.

Indeed, net trade restrained the U.K. recovery, taking 0.9 percentage points off growth over that period.

The household saving ratio - a measure of spending on goods and services, housing and financial services subtracted from income - has fallen its lowest point in over 50 years.

From the start of 2014, the fall in real wages went into reverse. While this was good news, what has surprised (and worried) economists is that the majority of these gains have been driven not by increases in the U.K. employment to record levels - and related wage gains - but due to falling consumer price inflation caused by oil's collapse.

What all this means: If household consumption depends on cheap oil, what happens should the crude market rebound?

Warning Signs

The question remains key to Britain's economic prospects. Despite rising household disposable income and buoyant sales, there are concerns that the boom will ultimately stall without a faster pace of earnings growth.

As the Office for National Statistics puts it in its latest data release on U.K. retail sales:

"Although the annual change in the quantity bought was strong (4.5%) between 2014 and 2015, the amount spent increased by only 1.1%. This could be explained by falling prices in stores, which decreased by 3.2%, as shown in Figure 2. Essentially, as a consequence of falling prices, consumers were buying more items which were costing less."

Amount spent, quantity bought and average store prices in the 4 main retail sectors, seasonally adjusted, 2015.

ONS

At the heart of the problem is the surprising lack of nominal wage gains, even with record employment.

It may be that the recession left workers timid in wage negotiations. Or low inflation may itself anchor wage demands. Whatever the case, with aggregate household savings already at record lows it will be harder to continue to fund the recent levels of consumer spending into 2016 absent a significant easing in credit conditions or a pick-up in earnings.

Even then, if consumers suspect current income gains are temporary - because of cheap oil - they may decide to rein in spending and build a rainy-day fund.

Another possibility is that low interest rates have opened up a savings deficit that households wish to plug before increasing spending on discretionary goods and services, such as jeans and dining out.

All of which bring us back to the looming prospect of higher interest rates.

After Governor Mark Carney's attempts to guide expectations of the timing of rate hikesfirst to the unemployment rate and latterly to a loose calendar commitment, the Bank of England has all-too-frequently had to reverse course and reassure the public and financial institutions that they are minded to hold off until wages and inflation pick up. As Kristin Forbes, a member of the bank's rate-setting Monetary Policy Committee, noted in a speech on Tuesday:

In the U.K., however, wages and labor costs have not yet gained enough momentum to be consistent with inflation reaching our 2% target. Tightening monetary policy today would require faith that our forecasting models will work and the tightness in labor market quantities and measures of labor market churn will soon translate into stronger wages and then higher inflation. But, unfortunately, these models have not been working very well recently.

In short, a significant chunk of the U.K. recovery still rests on the dual pillars of credulous households and collapsing commodity prices.

source: Bloomberg

source: Bloomberg

No comments:

Post a Comment