Even with policy rates close to—or, in some cases, below—zero, central banks in advanced economies have plenty of firepower left.

In the monetary experimentation with negative interest rates, central banks have proven that the effective lower bound is not zero—and according to Deutsche Bank, no central bank has cut rates as low as they can go just yet.

In theory, negative rates support loan growth through a carrot-and-stick approach. To the extent that they depress rates further down the curve, they create incentives for households and corporates to borrow. Meanwhile, by imposing a penalty on excess funds deposited at the central bank, negative rates push banks to make loans. If this penalty is passed along to depositors, the effect is similar, though potentially a double-edged sword—it's either conducive to current activity, or it provides an impetus to hoard cash, which carries with it an interest rate of zero.

It's a difficult Goldilocks act to pull off: Central banks have to set rates at an appropriately low level to buoy economic activity and meet their inflation objectives, but not so low that the populace flees to paper money to avoid a penalty. Such a development would severely impede the efficacy of monetary policy, effectively stripping the central bank of power.

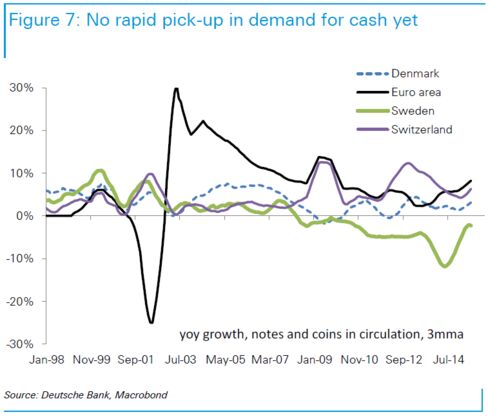

The key event for central banks—when they'll know that negative rates could be doing more harm than good—is when demand for physical currency spikes. And across member nations of the euro, plus Switzerland, Sweden, and Denmark, this has not yet come to pass:

Deutsche Bank

Deutsche Bank strategists Abhishek Singhania and Oliver Harvey offer a smorgasbord of evidence suggesting that negative rates have not been unduly punitive yet, and as such, we have not set our feet on the floor of central bank policy rates.

In the vast majority of cases, household and corporate deposits aren't subject to negative interest rates. "Imposing negative rates would not only risk damaging important relationships but [would] carry a disadvantage for the first mover, who could leach funding to competitors offering non-negative rates," the strategists wrote.

The costs are absorbed by banks and aren't too onerous, according to the pair.

"The direct costs to banks of negative rates appear small, even in economies with large amounts of excess liquidity relative to GDP," they wrote.

Central banks with negative policy rates have also capped the expenses borne by the banks by allowing excess liquidity above a certain level not to be subject to a penalty. Altering the threshold for exempt deposits provides a mechanism by which central banks can move rates more deeply into negative territory with more confidence that the costs won't be passed through to depositors to a degree that would prompt a run on banks and undermine the desired policy outcomes.

But another reason banks are fine with bearing the direct costs of negative rates is that they've found creative ways to pass the expense along in a less visible manner than attaching a negative rate to retail deposits.

Borrowers, not depositors, are taking the hit—although, of course, the vast majority of individuals come under both these labels, often simultaneously.

"The SNB have noted that the consequence of introducing negative rates earlier this year was rising, not falling, mortgage rates as banks sought to protect falling liability margins by raising long-end rates," the strategists wrote. "In a similar vein, Danish banks appeared to raise administration fees on new mortgages after rates first turned negative back in 2012."

Singhania and Harvey also observe that negative rates do not appear to be exerting much downward pressure on rates at the long end of the yield curve.

These dynamics demonstrate both how and why banks are able to cope with negative interest rates and how the efficacy of this tactic is blunted—where there are breakdowns in the transmission mechanism.

"This behavior also implies that negative rates are not an optimal tool for easing financial conditions," the strategists asserted. "Indeed, they could result in higher borrowing costs for the non-financial sector."

The primary channel by which negative rates have an effect on financial conditions is through the exchange rate. The real economy presumably gets a boost in turn as the competitive position of the external sector improves due to the currency devaluation that accompanies rate cuts.

"Short-end rates are more correlated to currency movements than long-end rates, likely because FX investors tend to fund positions using overnight or short-end rates rather than further down the curve," wrote Singhania and Harvey. "Negative rates have also proved to be more effective that outright currency intervention."

The strategists declined to offer a quantitative estimate for how low rates can go.

But as long as the global economy remains stuck in a stupor, this search for "absolute zero" will increasingly become a matter of practical necessity rather than of intellectual curiosity.

source: Bloomberg

No comments:

Post a Comment